Reading Tee-Shirts

Well into our third day in Haiti, while I was supposed to be looking for new product for the winter wholesale and retail show season, I will admit, I got distracted. It’s not that the art wasn’t great or that I wasn’t “into it,” but by late in the afternoon, my attention had started to drift. Instead of looking at metal sculpture, I was looking at clothing. Reading tee-shirts, in fact, and it was becoming good sport. I saw a Green Bay Packers shirt with a #4 on it – an old one, clearly. Brett Favre hasn’t played for them in 4 years now. But it’s a goodie, and hey, that’s my team! Go Pack Go! And I saw a Carolina Panthers jersey. Ooooh, not so much. But it wasn’t ‘til I noticed a tee-shirt reading “Nelson Family Reunion 2002, Lake of the Ozarks, MO” that I wondered, “How did he end up with THAT?”

Well into our third day in Haiti, while I was supposed to be looking for new product for the winter wholesale and retail show season, I will admit, I got distracted. It’s not that the art wasn’t great or that I wasn’t “into it,” but by late in the afternoon, my attention had started to drift. Instead of looking at metal sculpture, I was looking at clothing. Reading tee-shirts, in fact, and it was becoming good sport. I saw a Green Bay Packers shirt with a #4 on it – an old one, clearly. Brett Favre hasn’t played for them in 4 years now. But it’s a goodie, and hey, that’s my team! Go Pack Go! And I saw a Carolina Panthers jersey. Ooooh, not so much. But it wasn’t ‘til I noticed a tee-shirt reading “Nelson Family Reunion 2002, Lake of the Ozarks, MO” that I wondered, “How did he end up with THAT?”

Of course the answer lies in the practice of US charitable organizations sending bales and bales of clothing – to the tune of 14.5 million tons annually – to the Third World. According to www.planetaid.org only 20% of all clothing donated in the United States is actually sold in the United States to be worn. Five percent ends up in a landfill, and the rest is sold to wholesalers; 45% is repurposed (as cloth wipes, carpet backing, insulation, etc.) and 30% goes to market in developing countries. World Vision, for example, accepts 100,000 sweatshirts, tee-shirts and hats every year from the NFL, which routinely anticipates BOTH teams as the eventual winner of the Super Bowl and prints accordingly. The items that end up proclaiming the losing team as Super Bowl Champions go straight to the African continent.

So is that a good thing? Well, after due consideration, and a fair amount of research, I can tell you plainly that I don’t really know. There is well documented evidence that suggests that the overwhelming volume of textile donations from the Developed World, meaning the US, Europe, Australia, and parts of Asia, to the Third World is exceedingly detrimental to domestic textile and garment industries in the receiving countries. Case in point: A 2008 study done by Garth Frazer of the University of Toronto revealed that wealthy countries shipping tons of used clothing caused a 40 percent decline in domestic African clothing production and a 50 percent decline in employment between 1981 and 2000. The availability of free clothes from America and Europe undercut local markets and closed businesses. According to The Nation, between 1992 and 2006, 543,000 textile workers in Nigeria alone lost their jobs.

Furthermore, there are costs associated with this type of charitable giving. Again using World Vision as an example, it has been reported by Aid Watch that that organization spends 58 cents per shirt on shipping, warehousing, and distribution. This is well within the range of what a secondhand shirt costs in a developing country. The recommended alternative in each of these reports is to send money instead of clothing to meet immediate need. Goods purchased locally supports local producers and bolsters local markets. Additionally, it eliminates most shipping and transportation costs, which enables the donated dollar to go farther, i.e. it will buy more shirts and clothe more people. Local purchases lead to increased employment and a strengthened economy, ideally to the point where the needy aren’t needy anymore.

I tried and tried to find out how this plays out in Haiti. Haiti does, in fact, have a garment industry. Coincidentally, Bill and Hilary Clinton were in Haiti at about the same time we were (No, we didn’t get together for cocktails, but we’ll try to coordinate on the next visit!) to celebrate the opening of a new industrial park at Caracol, which includes a clothing piecework center that will potentially employ 65,000 people. An actual mill is slated for later development at this same site. Currently, however, this industry is piecework only. Workers receive pre-dyed, pre-cut tee-shirt “pieces” which they sew together for direct shipment to foreign markets, where they are sold by Walmart, Target and The Gap, among others. So it seems to me that, as of now, the importation of used clothing is not adversely affecting local production because the local production is for overseas markets anyway.

There is, however, a huge trade in Haiti that has been built around imported second-hand clothing. In fact, there is a Kreyol word for it: “Pepe.” According to Joanne McNeil’s blog article on reason.com, “It’s all pepe, all the time.” Pepe is sold on virtually every street corner in Haiti, yet it isn’t a  free-for-all. Vendors purchase goods by the bale for resale in ports such as Miragoane, where shipments are unloaded virtually every day. Often the dealers have an agreement with an American charity shop, which sorts the items before making the sale. Others rely on relatives and friends in the United States, who return to Haiti several times a year to make deliveries. Vendors typically specialize in certain kinds of goods—just soccer jerseys, just sneakers, just bikinis – but their total impact is such that 80% of all clothing bought and sold in Haiti is pepe. (Watch a trailer for a film on this subject here: http://secondhandfilm.com/project.html )

free-for-all. Vendors purchase goods by the bale for resale in ports such as Miragoane, where shipments are unloaded virtually every day. Often the dealers have an agreement with an American charity shop, which sorts the items before making the sale. Others rely on relatives and friends in the United States, who return to Haiti several times a year to make deliveries. Vendors typically specialize in certain kinds of goods—just soccer jerseys, just sneakers, just bikinis – but their total impact is such that 80% of all clothing bought and sold in Haiti is pepe. (Watch a trailer for a film on this subject here: http://secondhandfilm.com/project.html )

Well, that’s nothing, if not resourceful, in my book. It goes right along with the whole idea of recycling, reducing, and reusing. Admittedly, it’s not ideal. I’d like for them to have crisp, brand-new clothing, and tee-shirts that shout support for their own football (soccer) teams. But it is a legitimate trade, and it’s flourishing. It meets a need. And how bad is that?

Though I can’t say I’ve been anything close to EVERYWHERE, I am fairly well travelled. Travel for me is almost like breathing – I need to do it. Every issue of National Geographic, every vacation brochure in the mail, every song on the radio with an exotic beat compels me to think about my next trip. I’ve lived in eight different states and four different countries; I have been fortunate to visit many more. Still, for all of my presumed “worldliness” there is nothing quite like Haiti.

Though I can’t say I’ve been anything close to EVERYWHERE, I am fairly well travelled. Travel for me is almost like breathing – I need to do it. Every issue of National Geographic, every vacation brochure in the mail, every song on the radio with an exotic beat compels me to think about my next trip. I’ve lived in eight different states and four different countries; I have been fortunate to visit many more. Still, for all of my presumed “worldliness” there is nothing quite like Haiti. Do I like going there? Well, yes and no. Reading about the poverty and desperation is one thing. Seeing dirty, barefoot little kids with lice in their hair plinking rocks in the open sewer running in front of their house because they’ve got nothing else to play with is something else again. But then, you enter the shop doorway of one of our artists and you get a radiant smile and a great big hug and a whiff of Palmolive soap and find a tall cool

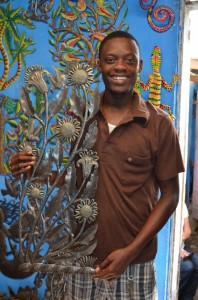

Do I like going there? Well, yes and no. Reading about the poverty and desperation is one thing. Seeing dirty, barefoot little kids with lice in their hair plinking rocks in the open sewer running in front of their house because they’ve got nothing else to play with is something else again. But then, you enter the shop doorway of one of our artists and you get a radiant smile and a great big hug and a whiff of Palmolive soap and find a tall cool  bottle of Coca-Cola thrust in your hand before you can say, “Jack Robinson.” And then they bring out amazing pieces of art. Their latest creations, wrought with such delicacy and brilliant craftsmanship and you can’t help wondering, “Where does this all come from?”

bottle of Coca-Cola thrust in your hand before you can say, “Jack Robinson.” And then they bring out amazing pieces of art. Their latest creations, wrought with such delicacy and brilliant craftsmanship and you can’t help wondering, “Where does this all come from?”![ht162[1]](https://blog.itscactus.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/ht16212.jpg)

![2179[2]](https://blog.itscactus.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/21792.jpg)

function in a manner that is sustainable, and thereby undercut aid dependency. Specifically, what her company was bringing to the table was a proposal to rehabilitate 15,000 hectares of existing cane fields, cleaning up watersheds, and revitalizing the one remaining sugar refinery in all of Haiti, the Darbonne Sugar Mill in Leogane. Increased production in that mill alone could potentially displace 50 percent of Haiti’s sugar imports and create 32,000 jobs. Additionally, by-products from sugar processing could be used as an energy source, with the possibility of putting out up to 20 megawatts of energy in the first 12-18 months of operation. With that, the circle could begin to close on deforestation, soil degradation, and erosion. Barjon said that the BioTek Agro-Energy Project would be financed by the International Investment Corporation (IIC), a private arm of the Inter-American Development Bank (IADB), and Haiti’s Sogebank, with potential underwriting from the Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC). She had the support of the Clinton Global Initiative and was working to get the stamp of approval from the Haitian Government to move the project forward.

function in a manner that is sustainable, and thereby undercut aid dependency. Specifically, what her company was bringing to the table was a proposal to rehabilitate 15,000 hectares of existing cane fields, cleaning up watersheds, and revitalizing the one remaining sugar refinery in all of Haiti, the Darbonne Sugar Mill in Leogane. Increased production in that mill alone could potentially displace 50 percent of Haiti’s sugar imports and create 32,000 jobs. Additionally, by-products from sugar processing could be used as an energy source, with the possibility of putting out up to 20 megawatts of energy in the first 12-18 months of operation. With that, the circle could begin to close on deforestation, soil degradation, and erosion. Barjon said that the BioTek Agro-Energy Project would be financed by the International Investment Corporation (IIC), a private arm of the Inter-American Development Bank (IADB), and Haiti’s Sogebank, with potential underwriting from the Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC). She had the support of the Clinton Global Initiative and was working to get the stamp of approval from the Haitian Government to move the project forward.