A Beautiful Tree and a Great Book (With a Haitian Connection) to Read Underneath

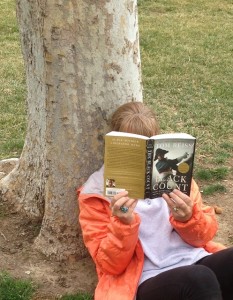

The shade of a beautiful tree is the perfect place to relax with book. Tree of Life by Wilson Etienne.

A beautiful tree and here’s a suggestion for the book to read underneath: “Black Count” by Tom Reiss. A page-turning biography, Reiss says he likes to think of the central figure as history’s greatest underdog. His book introduces readers to General Alex Dumas, the man that inspired so many fictional heroes of 19th century French literature, among them Athos, Porthos, Aramis, and D’Artagnan, of “The Three Musketeers,” and most closely, Edmund Dantes of “The Count of Monte Cristo.” These characters of derring-do sprung from the creative mind of the real son of the real “Black Count,” novelist Alexandre Dumas.

“Alex Dumas was a black man, sold into slavery in Haiti as a child, who eventually rose higher than any black man ever rose in a white society before our own time,” Reiss asserted in an NPR interview in 2012. “He became a four-star general 200 years ago, at the height of slavery.” This achievement almost defies comprehension, given that slaves in the French Caribbean colonies were appallingly mistreated and had an average survival expectancy of only 10 years.

To read under your tree, may I suggest The Black Count. Art and literature, two of life’s great pleasures!

The product of a union between the ne’er-do-well son of a white French marquis and a black slave woman, little Alex grew up on a small coffee plantation that his father had purchased in southern Haiti. He lived rather ordinarily, much as any boy of the colony would, playing in the jungles, fishing and exploring until about the age of 12 when his father abruptly sold him into slavery. Alex’ grandfather in France had just died, and his terminally cash-strapped father need money to pay for his own passage to France, where he could claim his title, inheritance, and lands.

Interestingly, once Alex’ father’s inheritance was secured, he sent for the boy through a repurchase agreement with the owner. After 2 years of enslavement, Alex sailed for France, the passenger docket listing him simply as, “the slave, Alexandre.” The timing was perfect. With the rallying cry in France growing ever louder, “Liberte, Egalite, Fraternite!” young Alex was welcomed into French society and provided with the best educational opportunities. He also learned war-craft, becoming an excellent marksman, swordsman, and equestrian. As an adult, Alex embraced the ideals of the dawning Revolution and took up its cause. His rise coincided with that of another young general of considerable talent: Napoleon Bonaparte.

General Bonaparte was more than aware of Dumas’ capable leadership, physical presence, and bravery in battle, and quickly came to regard him with adversarial jealousy. During the French army’s Egyptian campaign, Dumas and Napoleon’s rivalry intensified and the two clashed in a very public ideological disagreement. At that point, Napoleon’s jealousy evolved to a dangerous and vengeful hatred. On their way back to France, Dumas’ ship was diverted in a storm. He was kidnapped under mysterious circumstances and held for ransom, which Napoleon conveniently ignored. Dumas was eventually thrown into a fortress dungeon and forgotten.

Does it get more swash-buckling than that? Want to know what happens next? I’ve got two words for you: Read it!

Contributed by Linda for It’s Cactus

![2698[1]](https://blog.itscactus.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/26981-295x300.jpg) I wasn’t going to do this. I was going to do four articles on Voodoo. Four. No more. But to ignore the whole idea of zombies in four articles on Voodoo would be to ignore the elephant in the room. OF COURSE THERE ARE ZOMBIES IN VOODOO! I just wasn’t going to go into zombies because I thought they were too creepy and “out there,” running contrary to the kinder, gentler side of Voodoo practice that I was trying to convey. But then I read an article entitled, “A Zombie is a Slave Forever,” in the Oct. 30, 2012 edition of the New York Times by Amy Wilentz. A journalist and professor of literary journalism at UCal-Irvine, Wilentz described zombies so reasonably that they became, to me at least, more historically interesting than creepy. So here we are, with a fifth and absolutely final article in the “Voodoo Inspired” series. (Really.)

I wasn’t going to do this. I was going to do four articles on Voodoo. Four. No more. But to ignore the whole idea of zombies in four articles on Voodoo would be to ignore the elephant in the room. OF COURSE THERE ARE ZOMBIES IN VOODOO! I just wasn’t going to go into zombies because I thought they were too creepy and “out there,” running contrary to the kinder, gentler side of Voodoo practice that I was trying to convey. But then I read an article entitled, “A Zombie is a Slave Forever,” in the Oct. 30, 2012 edition of the New York Times by Amy Wilentz. A journalist and professor of literary journalism at UCal-Irvine, Wilentz described zombies so reasonably that they became, to me at least, more historically interesting than creepy. So here we are, with a fifth and absolutely final article in the “Voodoo Inspired” series. (Really.)![2637[1]](https://blog.itscactus.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/26371-163x300.jpg)