Owls of a Different Feather

Written for Patrick, because he asked…

Back in October, when I was in Haiti, I was looking at an intricate sculptural depiction of the voodoo ceremony at Bwa Kayman that set off the Haitian Revolution. There was a lot of symbolism worked into the scene, every detail fraught with meaning, so I was taking my time, looking it over very carefully and asking a lot of questions. When I spied an owl sitting in a tree, I asked our translator about its significance. Roosevelt’s face visibly darkened as he replied, “Oh owls are bad – very bad. Evil.” Then, he shook his head, “An owl has powerful black magic. You don’t ever want to mess with that.” I made a mental note to look into it further, and so here we are:

There are two different loas (Voodoo spirits) associated with owls. The first and by far the most ominous is Marinette, who takes the form of a screech owl and is clearly the one to whom Roosevelt referred. She is believed to have been the Mambo priestess that sacrificed the black pig at Bwa Kayman. Cruel, vicious, raging, and vengeful, she is greatly feared. She metes out justice with a powerful, violent hand and possesses the ability to free people from bondage or send them into slavery, at her pleasure. Knowing that after the Bwa Kayman ceremony, slaves slipped their chains to freedom while French slaveholders were slaughtered by the hundreds, it is clear that Marinette is not to be trifled with.

The second loa associated with an owl is named Brise, guardian of the hills and woodlands. Though he appears to be fierce, with large, dark, exaggerated features, he is actually quite gentle and loves children. Brise seems to be the basis of a widely recognized children’s folktale, which is elegantly retold in English in Diane Wolkenstein’s book “The Magic Orange Tree.” (For more on her book, click here http://dianewolkstein.com/projects/haiti-and-the-magic-orange-tree/ )

In the story, a shy owl encounters a lovely young girl in the woods at night. They talk and agree to meet again and again and during the course of their encounters, fall in love and agree to marry. The only problem is that the young girl has never seen the face of the owl and he is afraid to show it because he is ugly. He ends up flying away, alone, ashamed, and unwilling to believe that he could be worthy of a lifetime of love. The girl eventually finds a new love, but her happiness is forever shadowed by the melancholy of her previous loss. Far from being fierce and powerful, the owl in this story is self-effacing and unsure. Pretty significant contrast, I’d say.

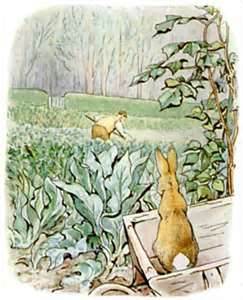

Then on the other hand, across the Carribean and a good bit of land mass are “my” owls; wise and all-knowing. What likely formed the basis for my line of thinking is a simple British poem written in the 19th century that I learned in second grade. Bet you did too:![il570xN264988494[1]](https://blog.itscactus.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/il570xN2649884941.jpg)

“The Wise Old Owl lived in the oak

The more he saw, the less he spoke.

The less he spoke, the more he heard.

Why can’t we be like that wise old bird?”

How different my impression of owls is from those depicted in Haitian lore! It has nothing to do with the bird itself and everything to do with the stories I was told as a kid. Cultural heritage. Pretty interesting, isn’t it?

Contributed by Linda for Beyond Borders/It’s Cactus

![2706[1]](https://blog.itscactus.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/27061.jpg)

![rnd298[2]](https://blog.itscactus.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/rnd29822-300x298.jpg)

![rnd458[1]](https://blog.itscactus.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/rnd4581-300x294.jpg)

![rnd292[1]](https://blog.itscactus.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/rnd2921-300x297.jpg)

![9989448953c75b22[1]](https://blog.itscactus.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/9989448953c75b221.jpg)

![200px-John_James_Audubon_1826[1]](https://blog.itscactus.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/200px-John_James_Audubon_182611.jpg)

![sm413[1]](https://blog.itscactus.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/sm41311-133x300.jpg) When a sculpture is selected to be sold in the Beyond Borders catalogue or on our website, we photograph it, give it an inventory number, and a name. This one, for what may be obvious reasons, we chose to name “Double Trouble.” The impish looks on these faces, the hair standing on end, the shape of the mouths – all of that said, “Uh-oh” to us. “Double Trouble,” absolutely. It’s cute, it’s catchy. Maybe someone with twins will buy it.

When a sculpture is selected to be sold in the Beyond Borders catalogue or on our website, we photograph it, give it an inventory number, and a name. This one, for what may be obvious reasons, we chose to name “Double Trouble.” The impish looks on these faces, the hair standing on end, the shape of the mouths – all of that said, “Uh-oh” to us. “Double Trouble,” absolutely. It’s cute, it’s catchy. Maybe someone with twins will buy it.![image005(231)[1]](https://blog.itscactus.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/image0052311-220x300.jpg)

![images[1]](https://blog.itscactus.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/images1.jpg) They successfully grafted the leg of a recently dead black man onto a disabled white man, who was thus able to walk again.

They successfully grafted the leg of a recently dead black man onto a disabled white man, who was thus able to walk again.